The Yamuna and her tides become symbolic of the horrific future of the Maratha empire. Patil strikingly describes how Nature itself seemed to be against the warriors. Ultimately, this turned out to be the Marathas’ biggest weakness. If the religious tinge smote hearts, the tales of betrayals deepened the wounds. This furthered the already existing gaps between different sects and strong animosities were now built within the armies and these internal squabbles, in a way, unintentionally paved a clear path for the rise of the British power in India in the late 18th century. The battle did not decide who was to rule India but rather who was not to. Vilification campaigns were carried out on a great spree, and there was no possibility, though several attempts were made, of arriving at a truce. The war was given a religious colour and the chants that reverberated on the grounds of Panipat embraced the gods in a manner that was more poisonous than spiritual. The distinction between right and wrong had vanished. Though the Afghans emerged victorious in this war, they couldn’t rule the country. It also narrates how the great battle changed the power equations in India. The narrative effectively highlights certain aspects like the lack of the Marathas’ ability to persuade the masses, the capability of the Afghans to lead from the front and the role of women and children in the entire ritual of war. The Maratha plan didn’t work out well, and soon, the majority of the army was defeated by dwindling resources and grave hunger. The Marathas, led by Sadashiv Rao Bhau and his ally Ibrahim Gardi, used European fighting tactics Abdali’s army made up for their lack of field artillery in brutally effective mobile artillery - the tough foot soldiers. The battle is noteworthy in terms of the war strategies adapted. The first two battles of Panipat mark the beginning of the spread of the Mughals in India, but the third battle, which was fought between the Marathas and the Durrani empire, is etched as one of the biggest and most significant battles in India in the 18th century. In a sense, it encapsulates an epoch of both belief and incredulity.

Today, the Third Battle of Panipat is seen as an event that reminds us of the resilient and unyielding spirit of the Maratha soldiers. Although the forces and allies of the Afghan ruler Ahmad Shah Abdali wangled victory, it was evident that the Afghan empire too was overwhelmed by the buoyant Maratha forces.

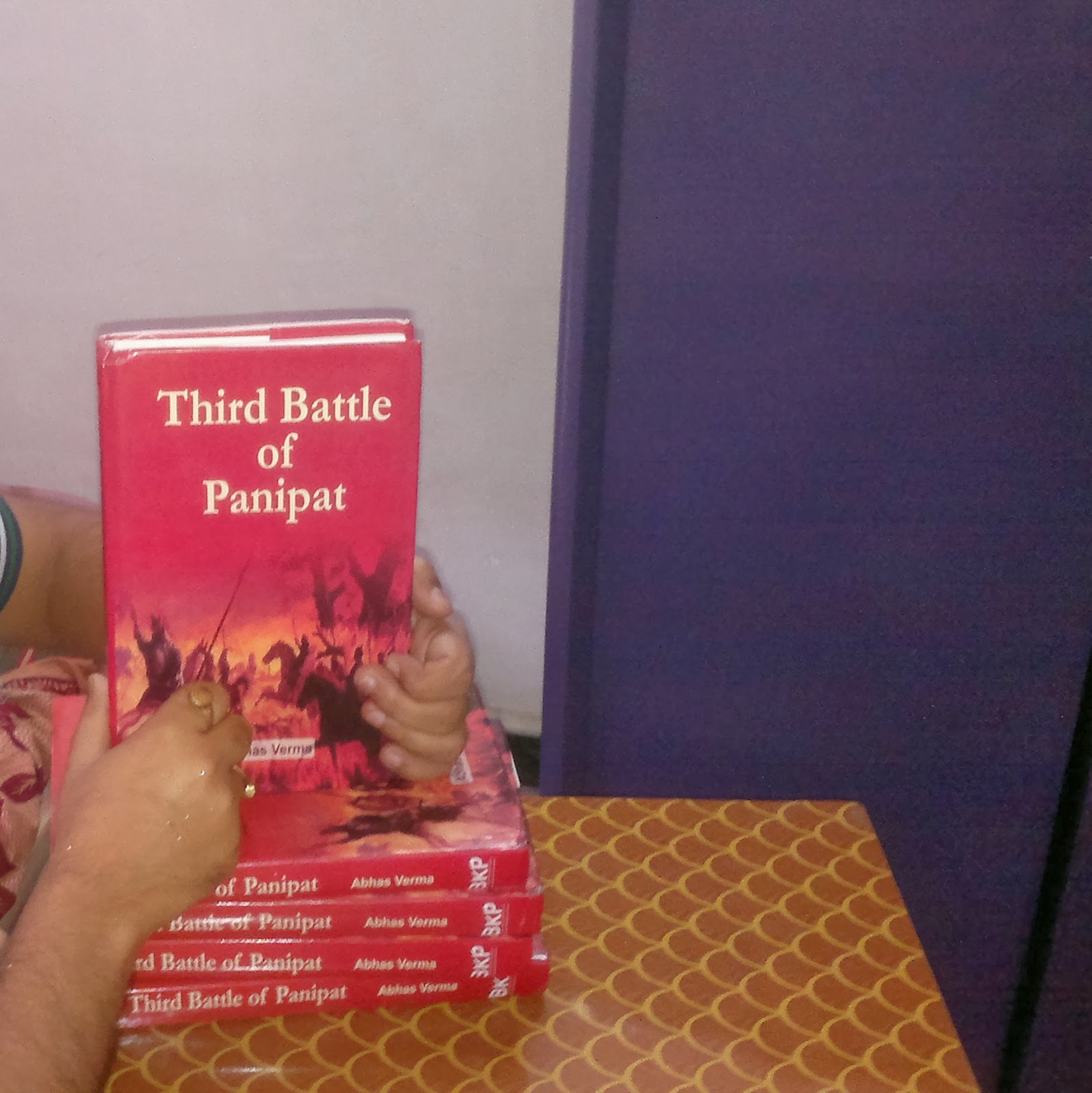

The publication of Vishwas Patil’s Marathi novel Panipat (1988) and its subsequent translations into Hindi and other regional languages went a long way in changing the perspective of its readers towards this historical episode. The defeat of the Marathas at Panipat has gone down as a disastrous and a shameful event in the annals of Indian history.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)